> Too many floodgates: analyzing Floxif

(12/28/2025), 5 minute read ⏰

Note: these are just my markdown notes, but a bit cleaned up. The original sample link is there too! Feel free to check out the original notes here!

I am back with another piece of malware to analyze, this time, from a friend of mine who does not go by deluks. He checked out my AlmondRAT writeup and suddenly stated: "Oh ye u should reverse floxif".

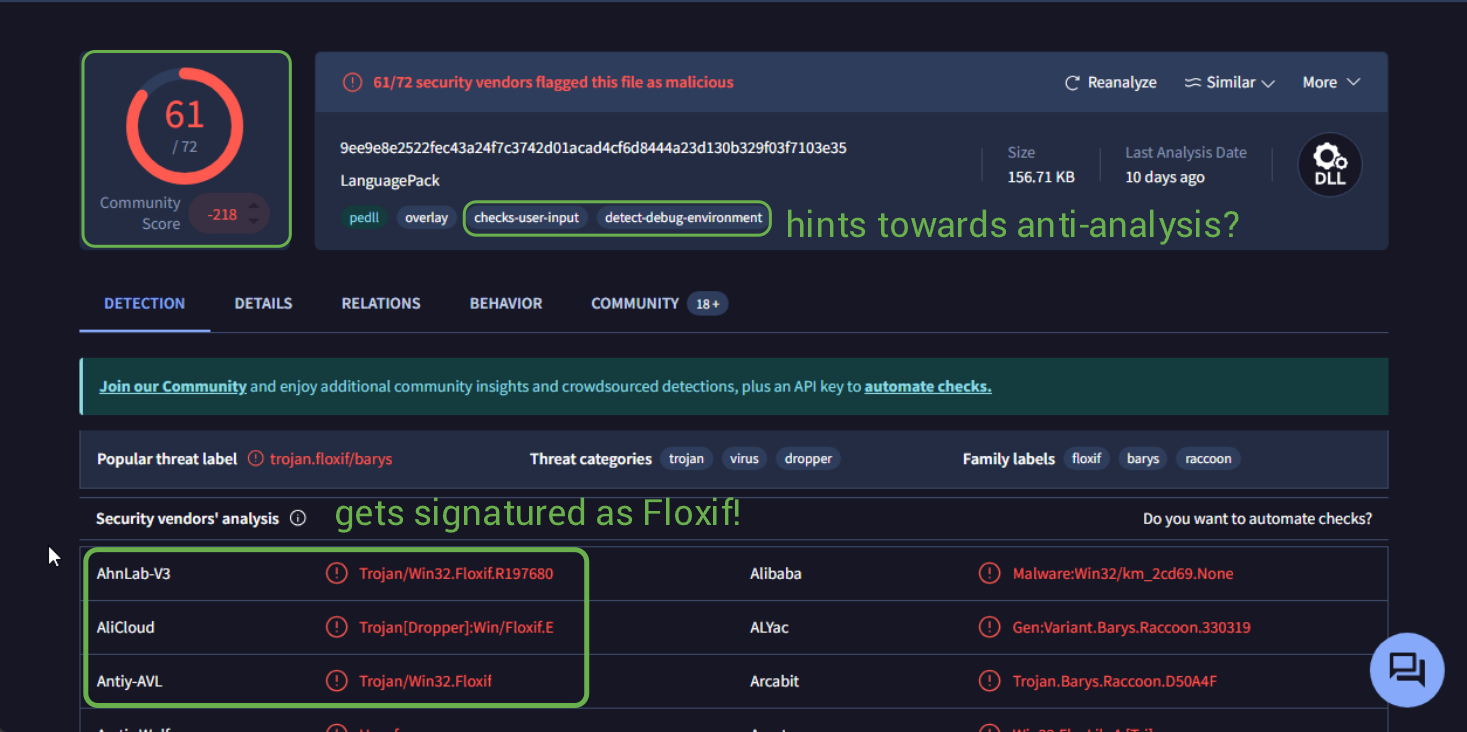

In all honesty, there are many samples of "Floxif" laying around. vx-underground doesn't have any (from what I can see), and MalwareBazaar has many samples tagged with "Floxif", so I just picked the top result at the time of writing.

As with previous analysis, let's define our protocol to work off:

1. Determine if the sample is packed or not (using DiE). Unpack as necessary. Perform some basic fingerprinting (SHA256 hash, packer info, resources, file type, compiler, imports/exports and strings.)

2. Run the binary through a sandbox (VT once again.)

3. Decompile the sample (check for dynamic API resolution, obfuscation, shellcode, etc.) If we encounter any sort of obfuscation, we'll try to identify a way around it.

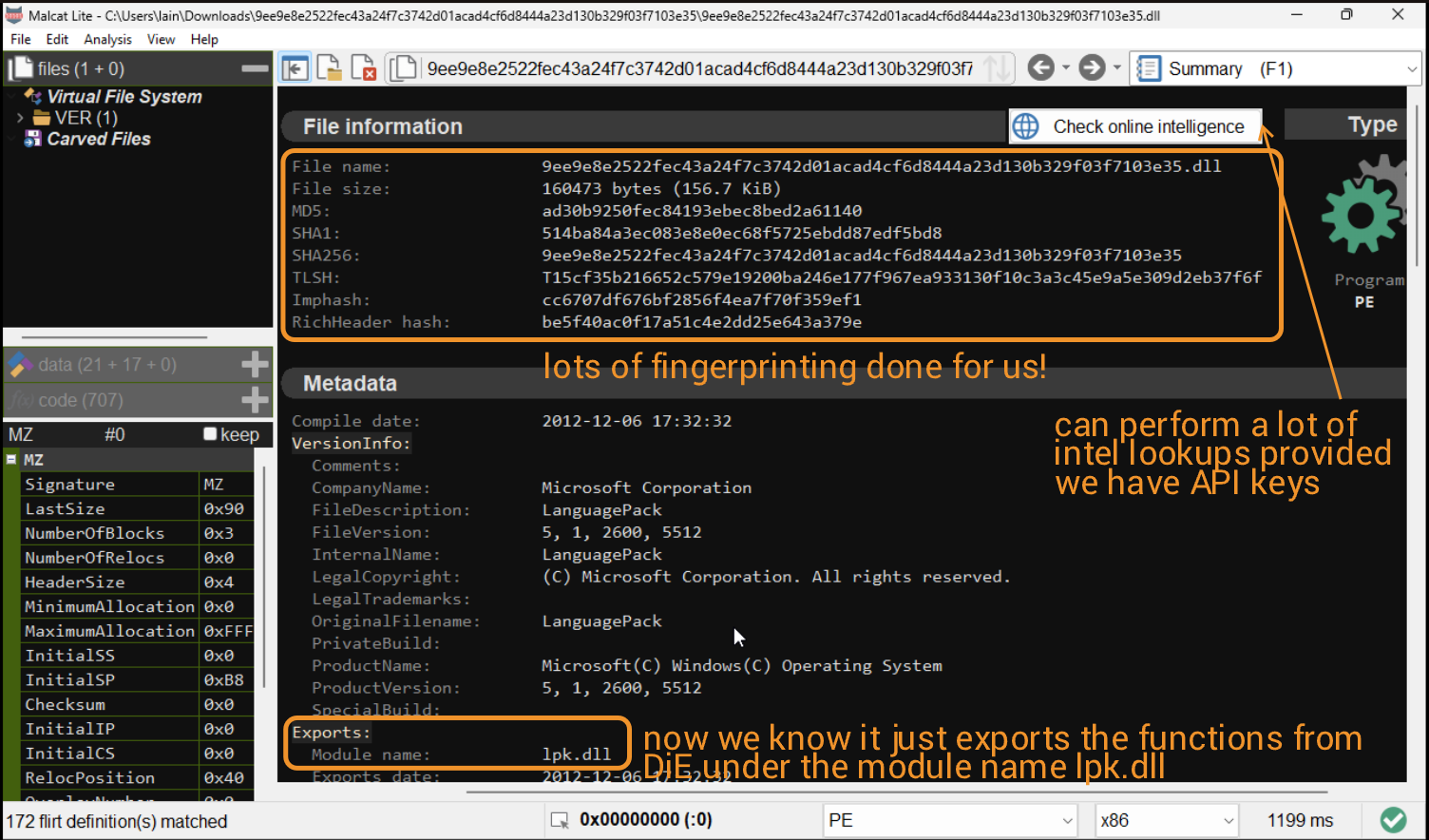

Because this is a DLL according to MalwareBazaar, we will be using Binja and Malcat for the first time in this analysis. We will start with Malcat to perform a basic disassembly, then swap to Binja as needed.

With all that being said, let's begin!

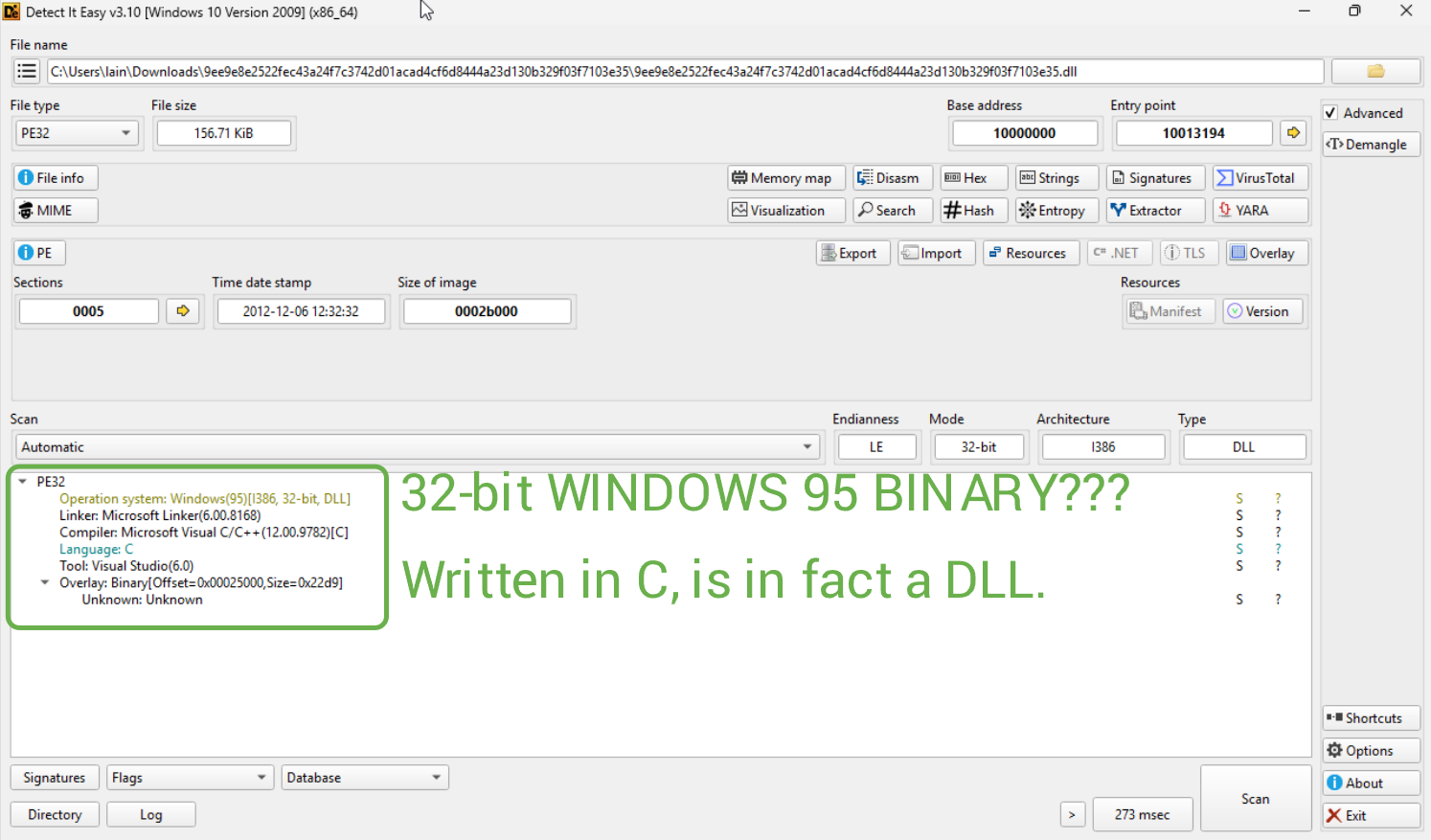

Let's load the sample into DiE and extract some information from it.

Let's tick off some fingerprinting steps:

- No packers were detected (in fact, MalwareBazaar shows that this sample was originally packed using UPX, and this is the unpacked sample, so this is expected)

- We have the SHA256 hash provided by MalwareBazaar

- We know its a DLL, written in C, compiled w/ MSVC

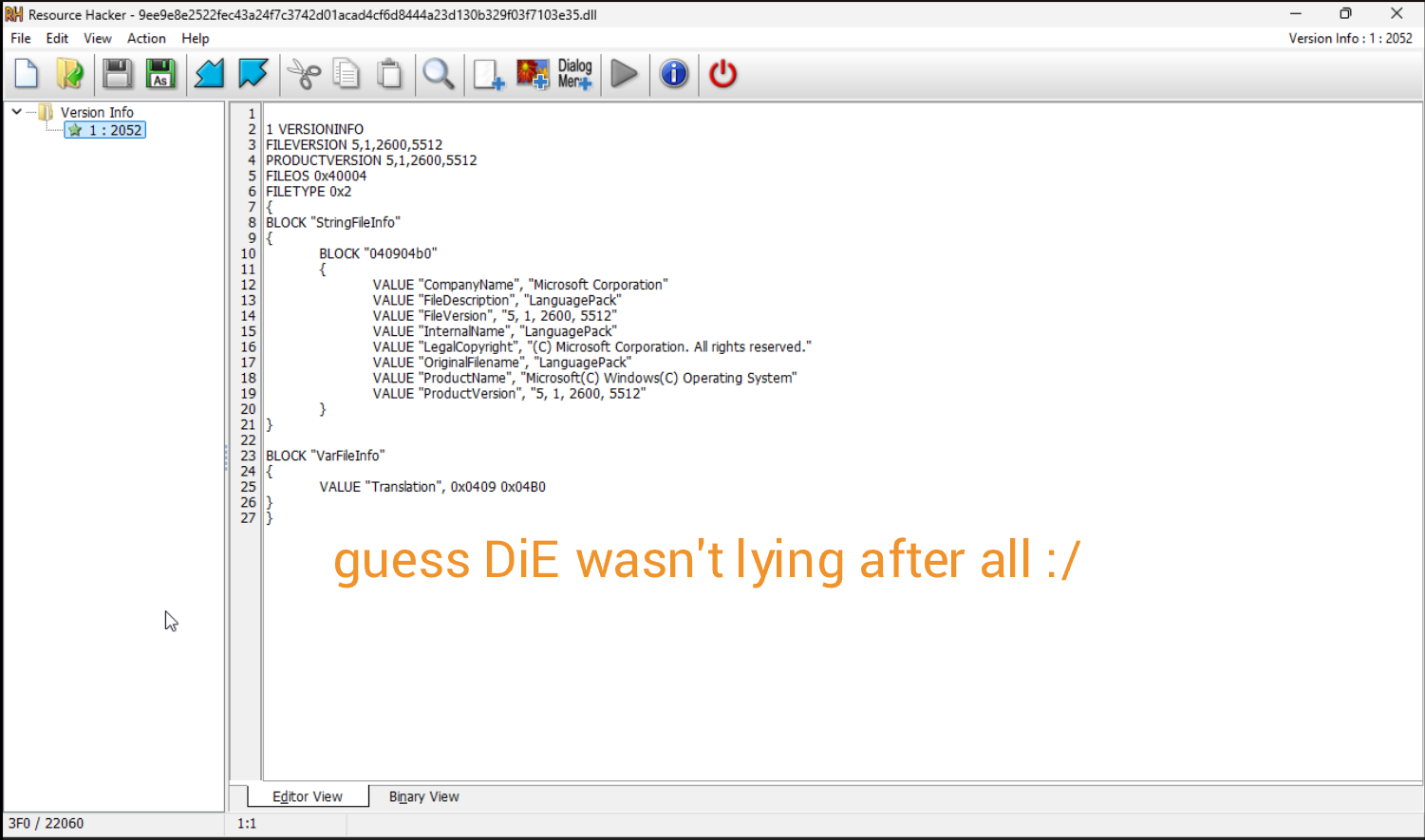

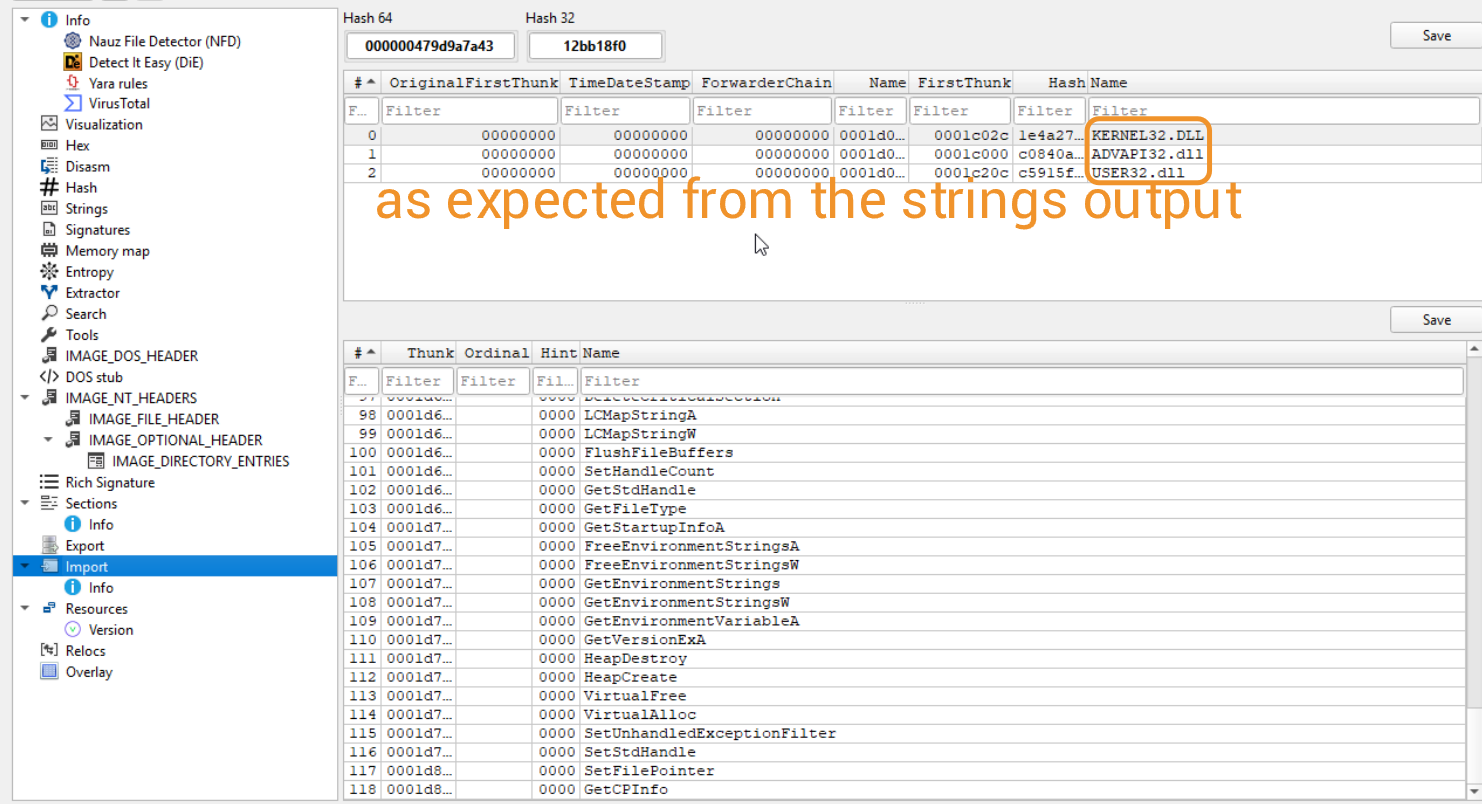

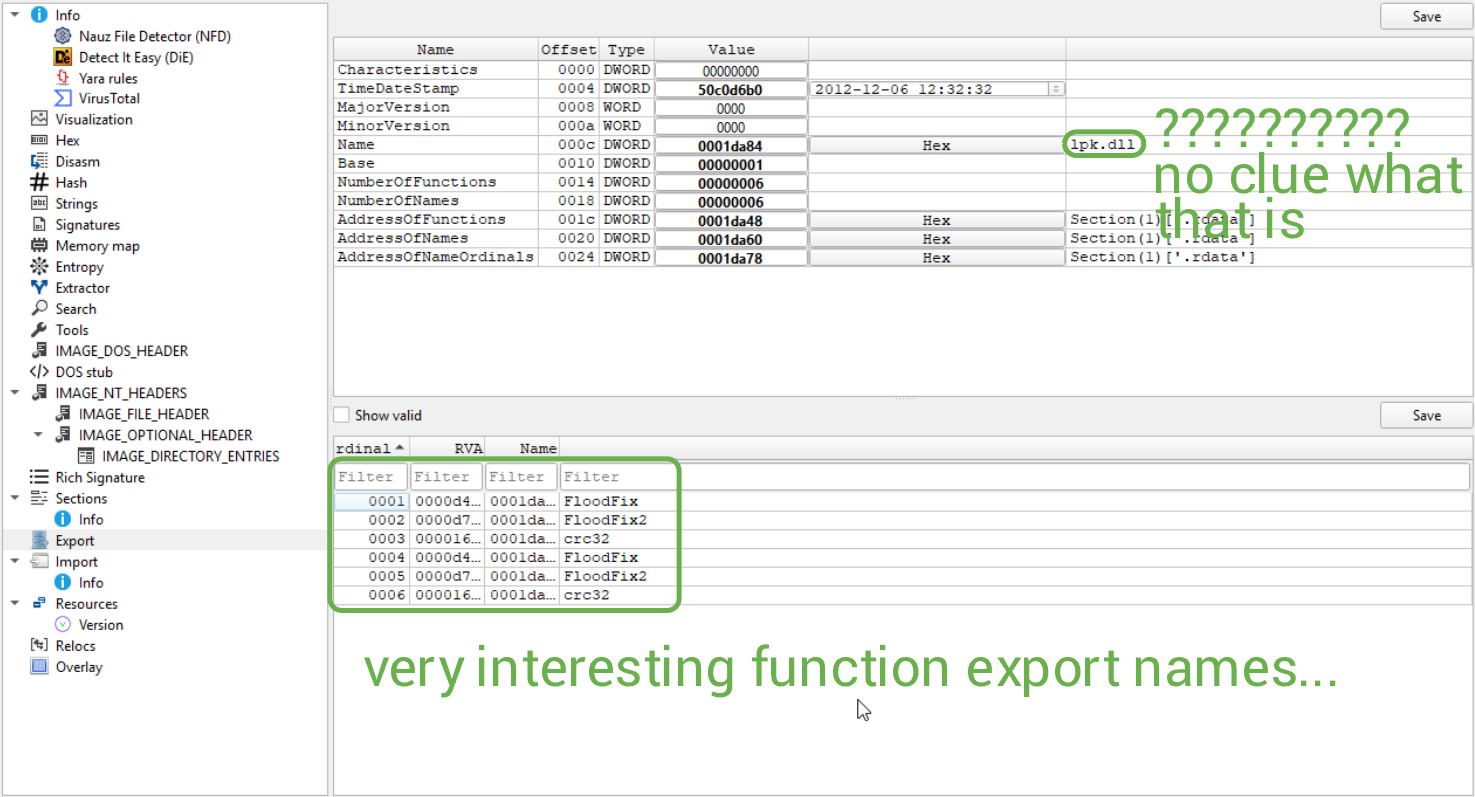

Let's look for our remaining artifacts (strings, resources, imports/exports). Because this is a DLL, there should naturally be some (at least one) export from it (i.e. to some kind of main function, like DllMain).

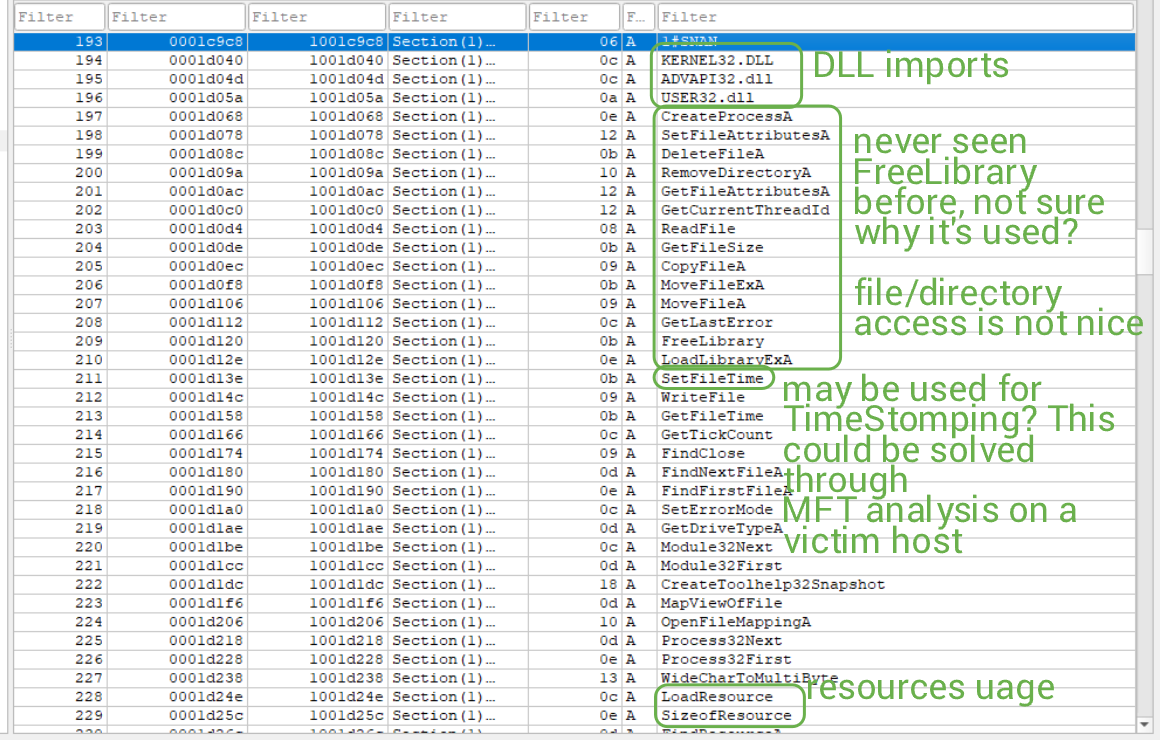

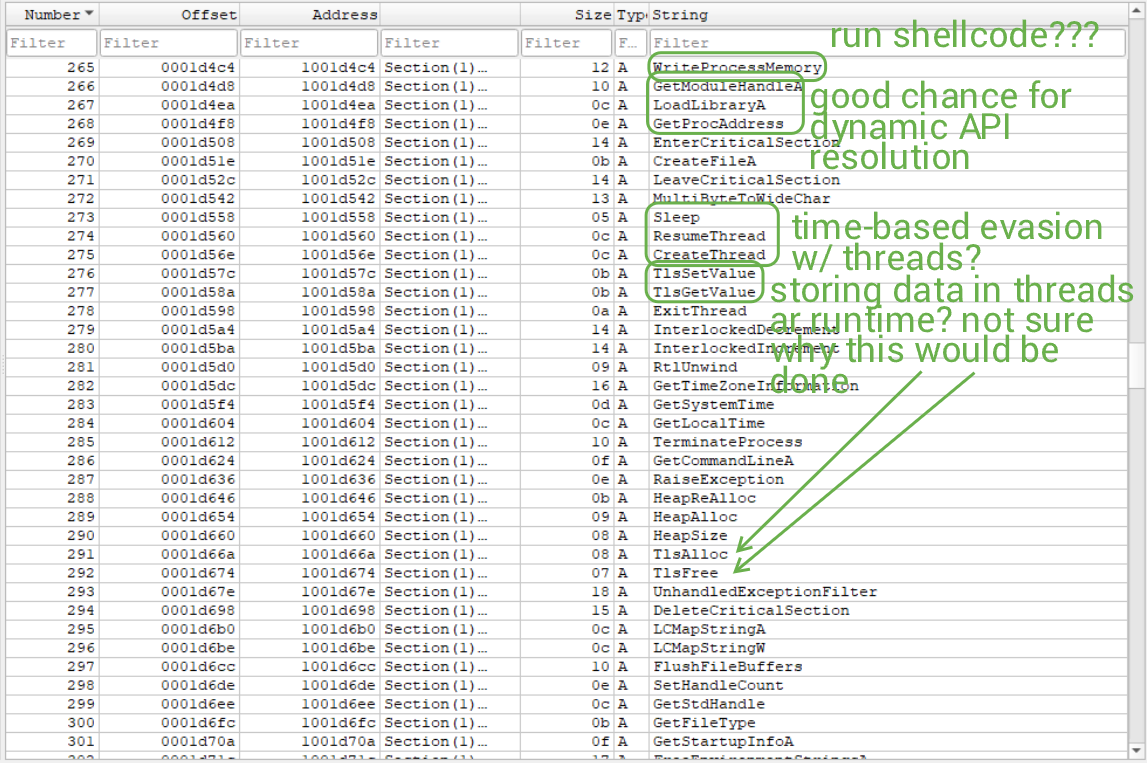

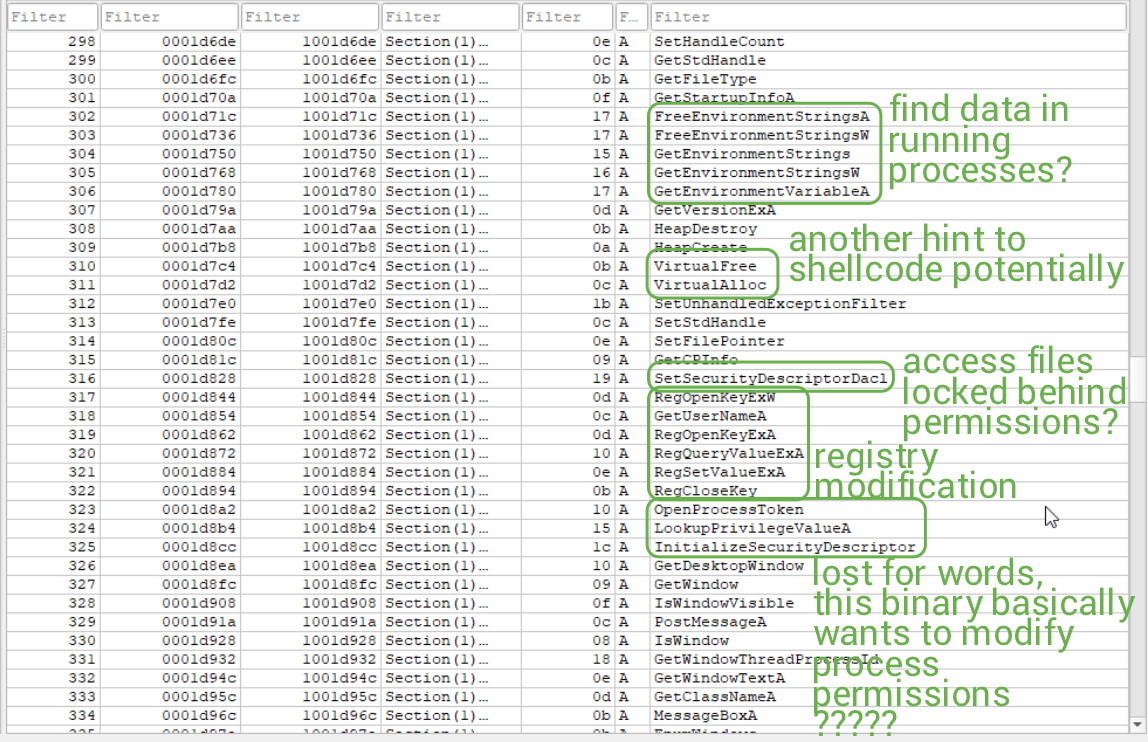

The strings in this binary are a bit bizarre. We can see many WinAPI functions, including LoadLibraryExA, but also FreeLibrary.

This is very alarming (to me). The amount of STUFF occurring in this sample is crazy. What's most interesting and terrifying to me is that the binary (supposedly) enumerates currently available permissions for the session, and a given process (by viewing its access token), and attempts to modify the security token DACL (maybe?). I'm certain I'm making mistakes here in my assumptions, but I think you (the reader) and me can agree that this is not pretty one bit.

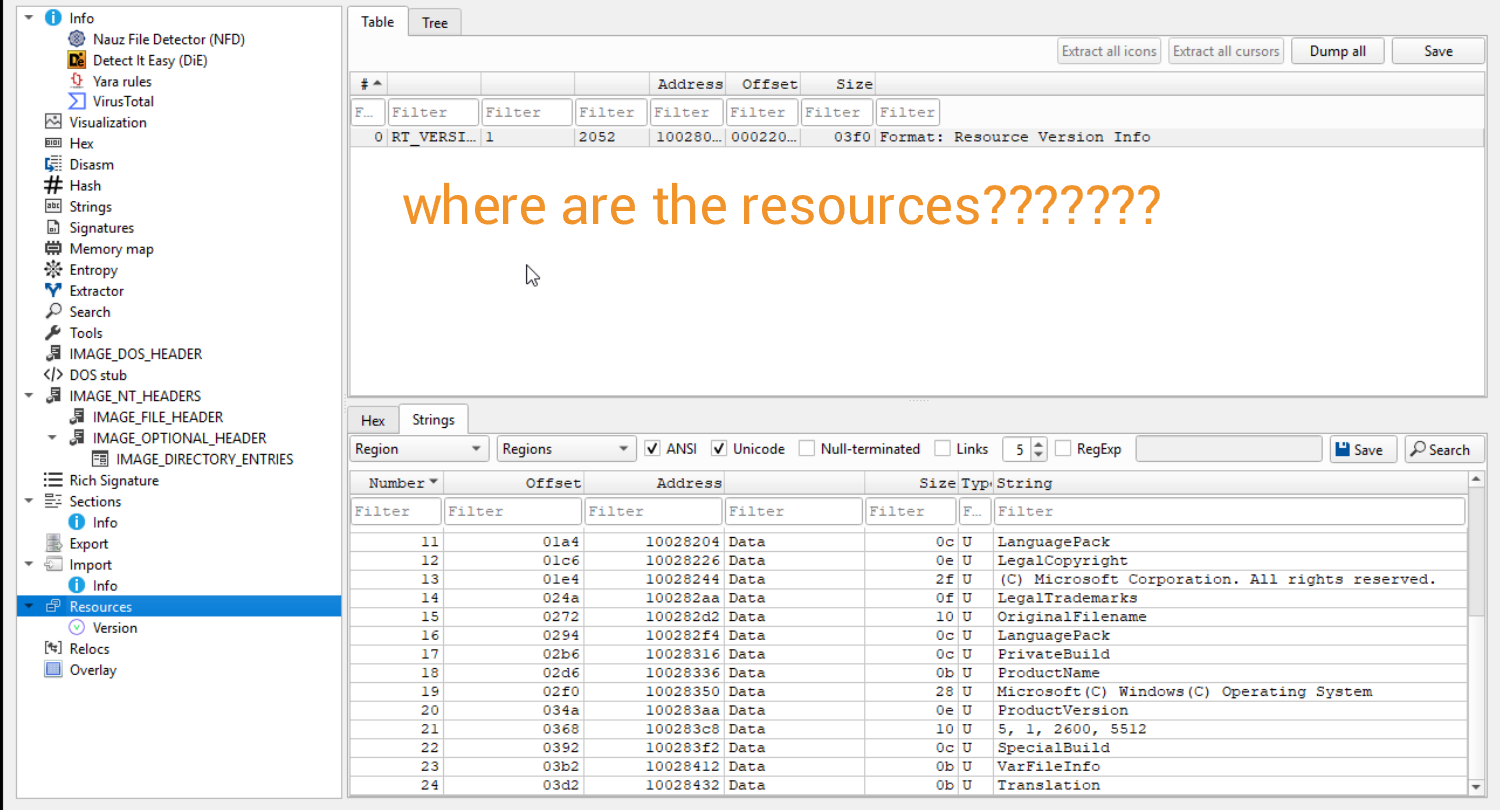

Continuing with our analysis, let's check the resources in this binary, since our strings are showing that some resources are available.

Either I'm blind or DiE is lying to me, so I decide to open up Resource Hacker and load the binary.

At least we can confidently say there isn't anything immediately found. We'll finish off our analysis w/ DiE by looking at the imports and exports.

My knowledge of DLL exports is a bit weak, so feel free to shoot me an email or message me on Discord about what my findings really mean.

We're finished our first step of analysis. The next step is to shove the binary into VT and see what quick wins we can get.

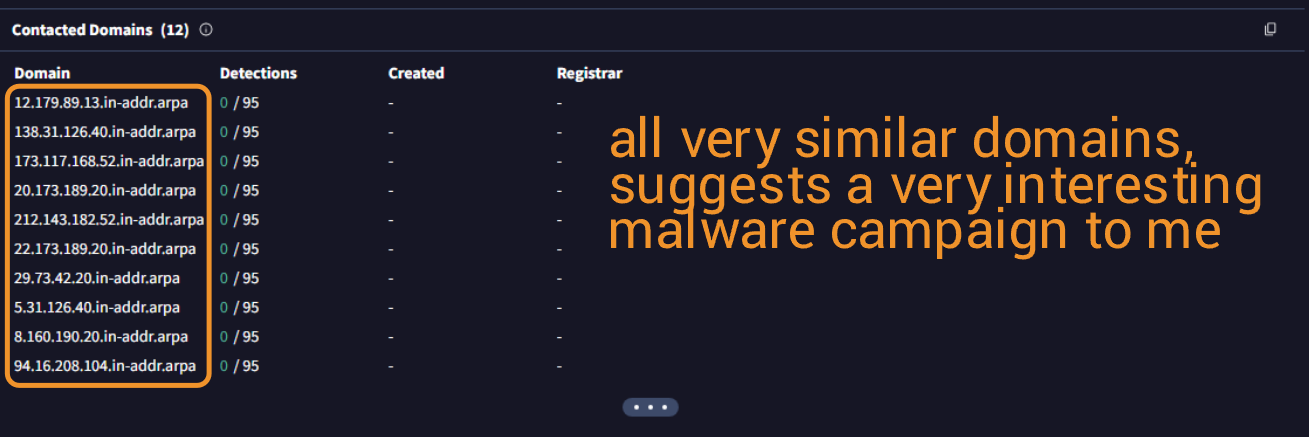

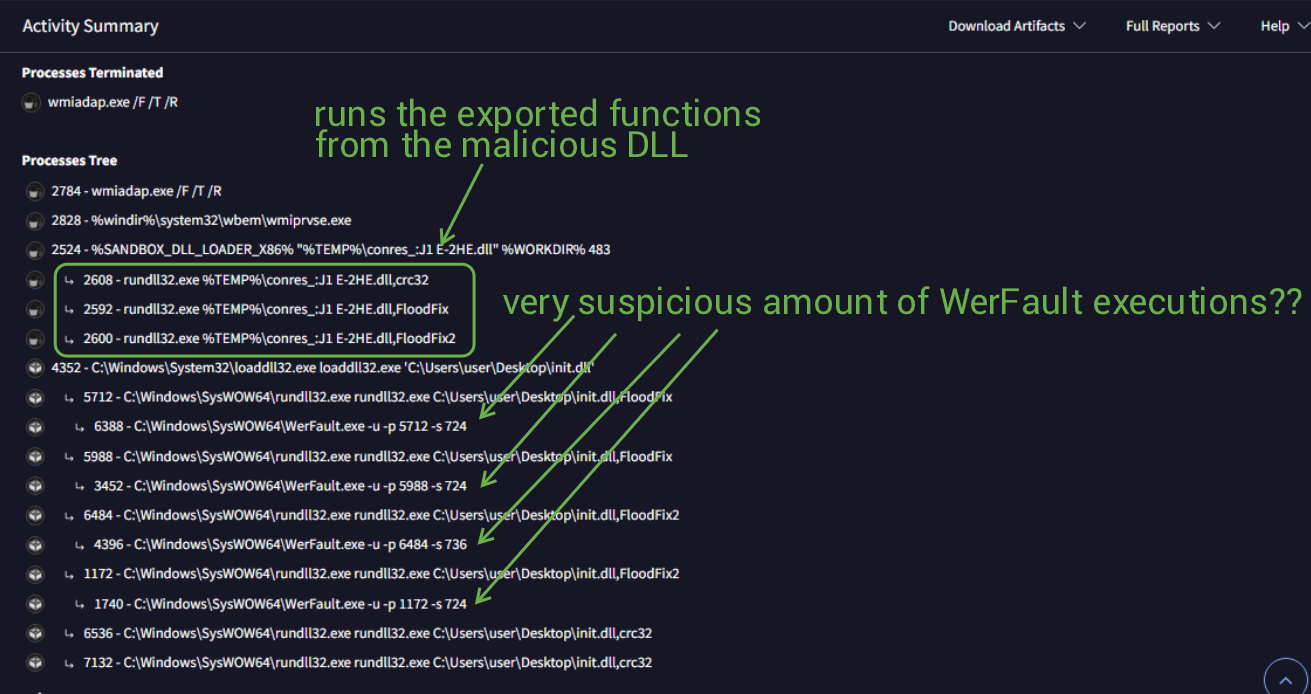

There's a lot to take in here. If we wanted to know if this was malware. We've already collected more than enough information. There are 2 things I left out from my images/findings here. 1) ~20 dropped files come from this program and 2) there are numerous registry key modifications. A lot of these have to do w/ rundll32.exe for some odd reason, and I'm unsure what they all mean.

Let's continue on to the last step of our protocol, which is some static analysis.

Firstly, I'm gonna try loading the binary into Malcat, mainly to check if it can extract more findings for us, but also to check a bit of the disassembly, and show off the tool for once.

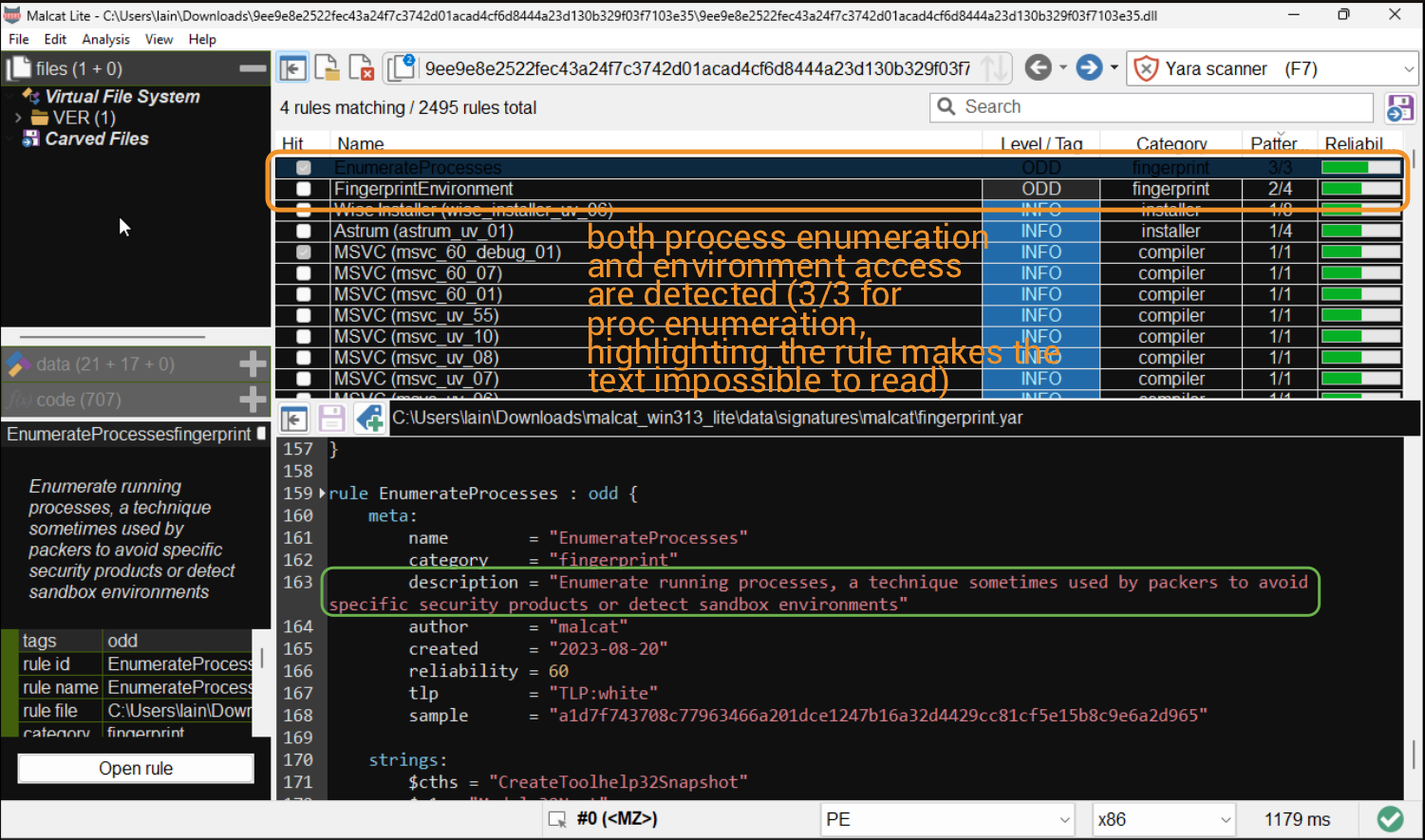

No, I was not sponsored by Malcat (though that'd epic) to absolutely glaze their product, I'm just impressed at how good it is. We can see that some built-in YARA rules also inform us that the binary attempts to access the OS environment and enumerate other processes.

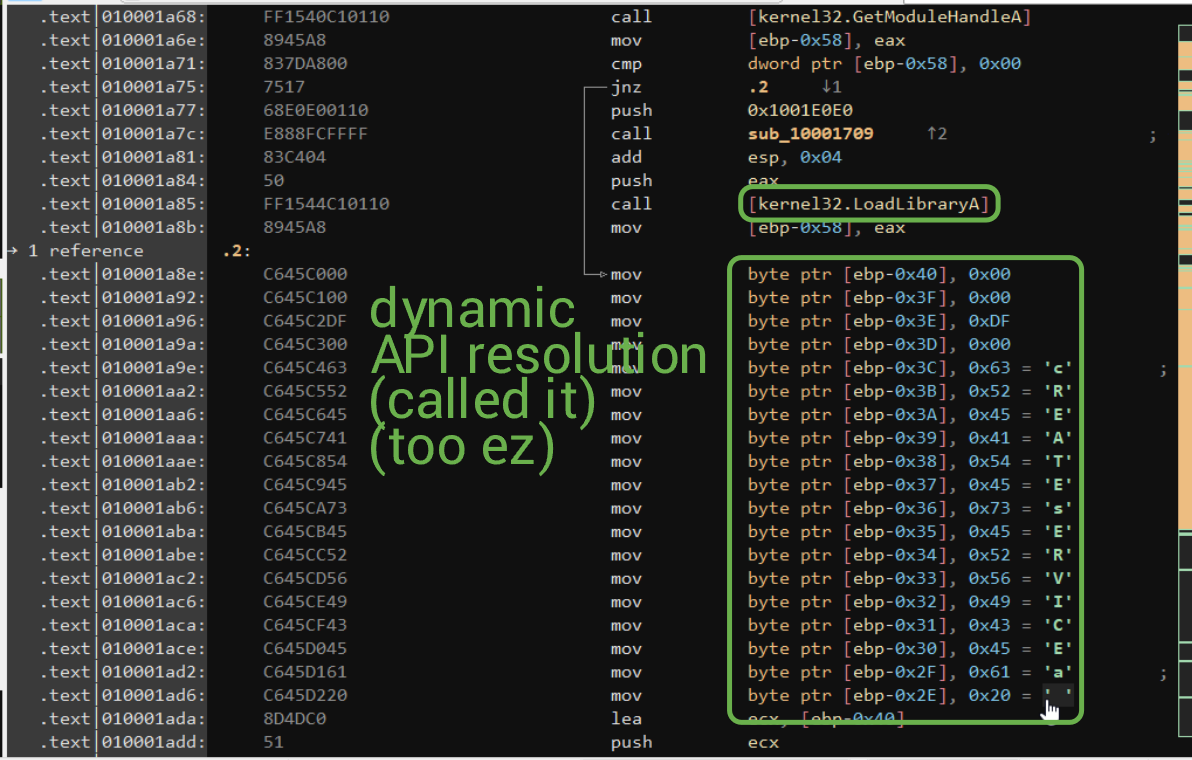

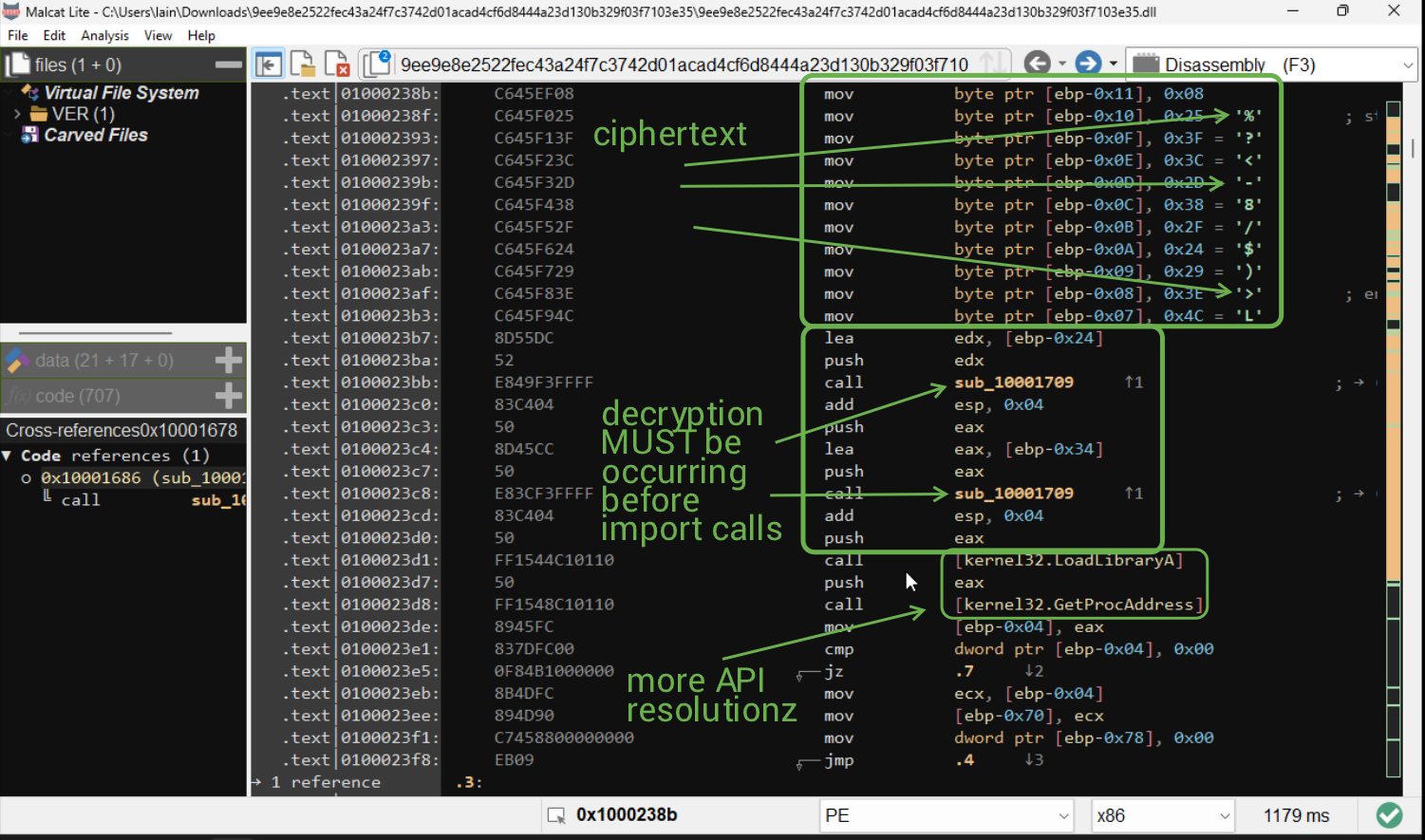

I decided to check out the disassembly from here, and what I witnessed was pretty hilarious.

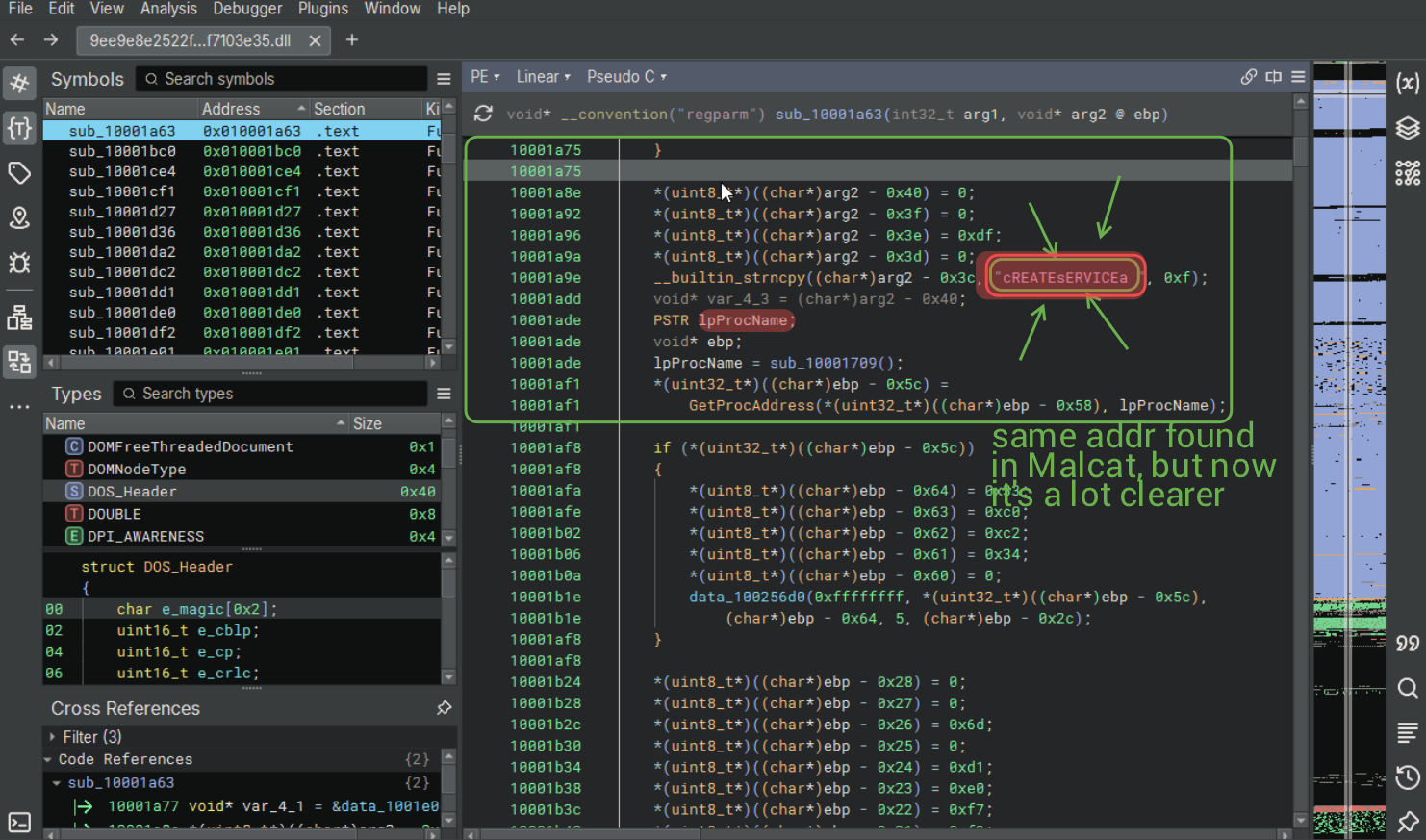

Self explanatory enough. There are many other points where mov byte ptr [ebp-(some offset)], (ASCII in hex) operations are done, followed up by what looks like some decryption operations.

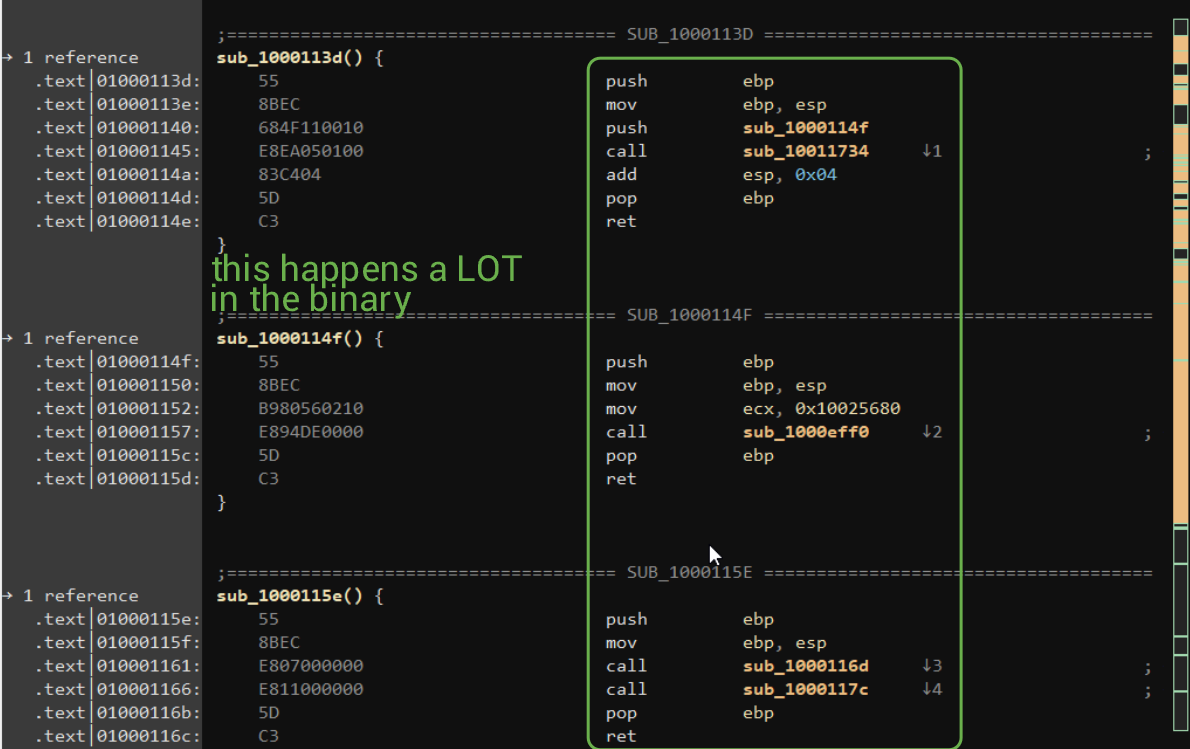

I also found some very odd behaviour with subroutines near the beginning of the .text section:

My good friend deluks spoke to me about opaque predicates recently, and I felt like this was somewhat similar. To me, this is a form of anti-analysis to a degree, more so "let's make the CFG painful to view", since there are just calls upon calls upon calls to subroutines that seemingly do nothing.

I kept looking through the disassembly but honestly, I cannot be asked to figure out everything that's going on. Our only real option is to load this into Binja and see what more we can figure out (spoiler, basically nothing).

The same friend that I referenced at the beginning of this article joined a call with me for this portion of the writeup. We spent some time trying to look into the binary w/ Binja but to little success. We decided to look further into the CreateServiceA call made and jumped to its address in Binja. We noticed that this binary loves to screw up the stack.

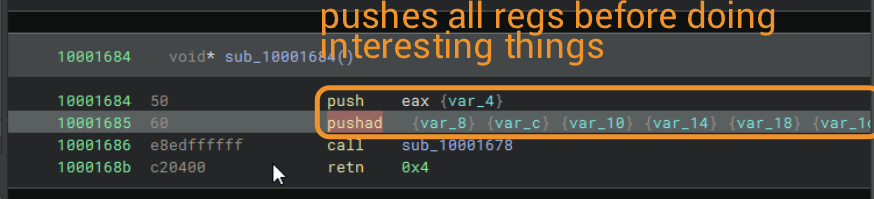

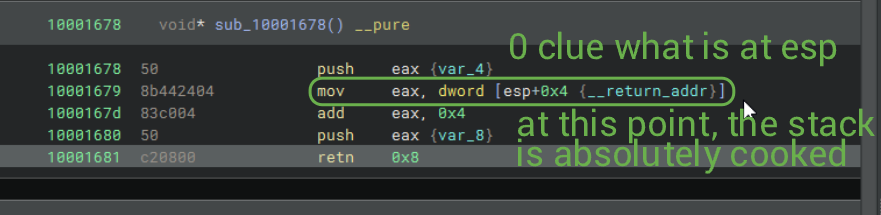

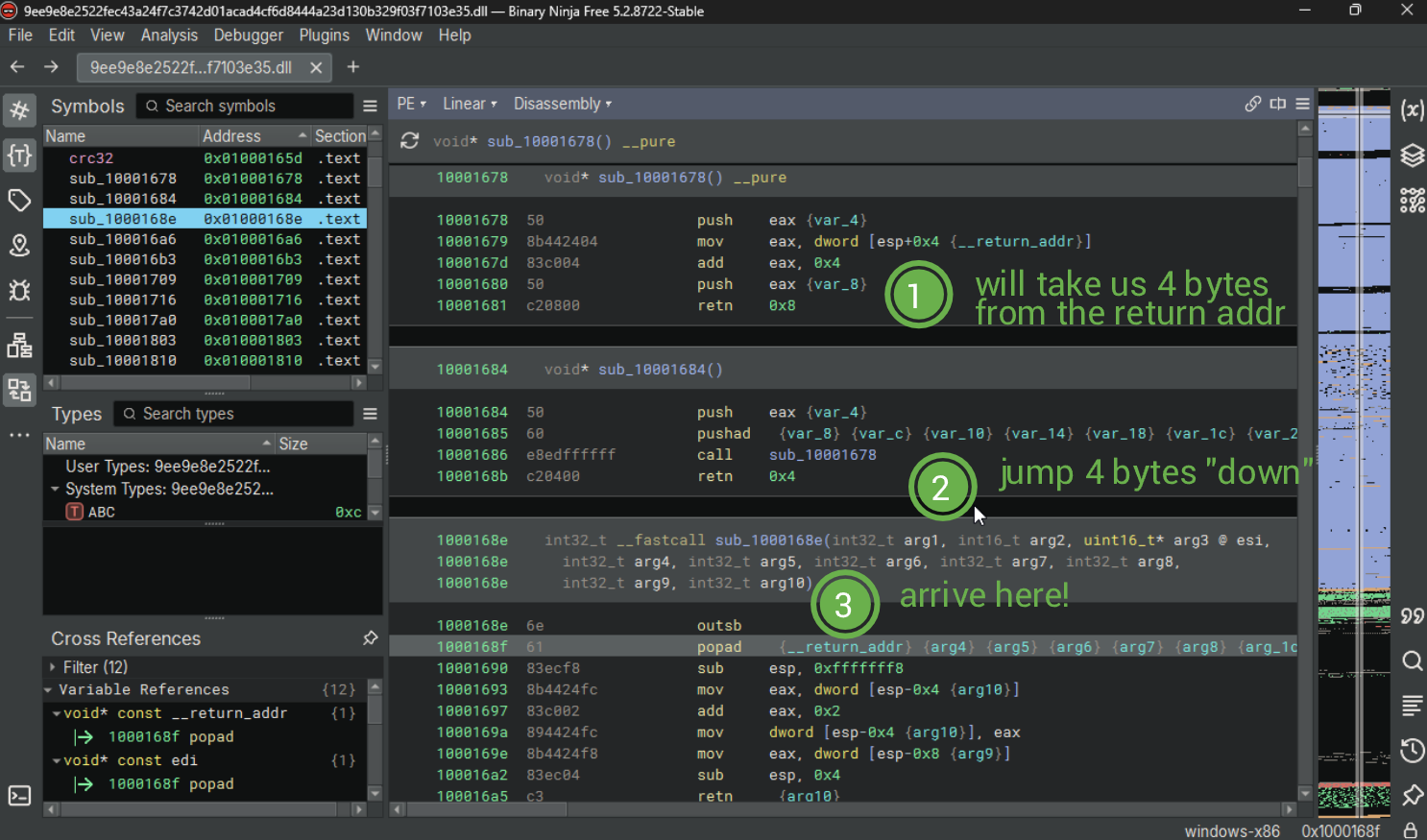

Given my state of distress, I called upon my good friend deluks once more. What's actually happening here is that we skip ahead 4 bytes. We push eax (whatever's in it, probably to save its value for later), save the return address of this function (mov eax, dword [esp+0x4]), add eax, 0x4 to skip ahead 4 bytes, push it, then retn to return. ret/retn are basically shorthand for pop rip (pop eip for 32-bit). So what actually happens is rip = __return_addr + 4. At the next ret instruction, we will go back to the original return address from this subroutine, assuming we do not pop off eax = __return_addr elsewhere.

This is a very annoying manner of control flow obfuscation. Note: The 1st and 2nd markers below are swapped by accident!

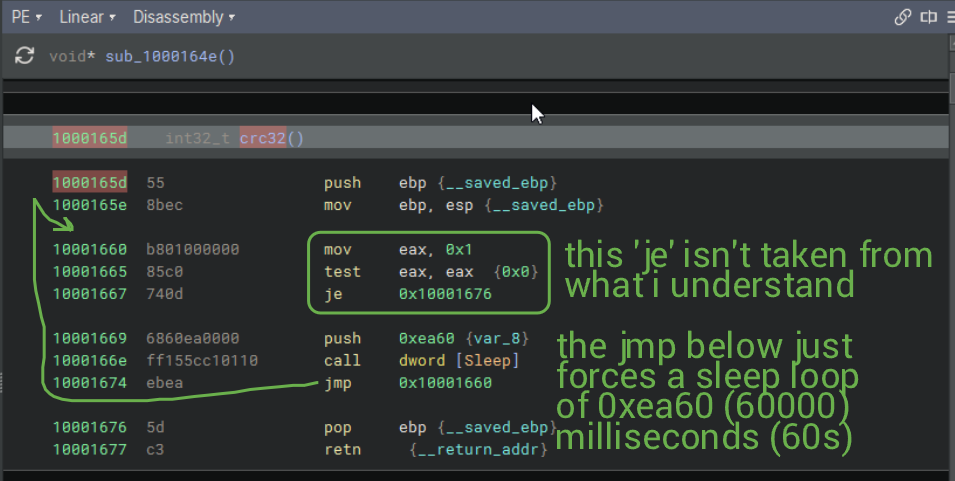

Interestingly enough, both the FloodFix and FloodFix2 export functions runs this exact bit of code. The crc32 export looks like the following:

This is where I'm going to end my writeup for this sample, since yes, I'm too lazy to continue analyzing this, but also because I just don't know where to continue.

My stance on this sample is that there's a lot more to discover through dynamic analysis and debugging over painfully attempt to statically analyze this (lots of branching calls and stack trickery I don't like). Am I content with what we found? Sort of? We didn't actually figure out what kind of malware this binary is either. I'd say the closest resemblance this sample has is that of a loader or some sort of file infector.

If you (the reader) believe there is more to this sample, then feel free to send me an email or reach out to me on Discord. I will edit this writeup if I find out more about this sample as needed!

Edit (A few minutes after publishing)

Turns out that Floxif is a malware family of file infectors (infecting Windows executables/DLLs) which creates backdoors for more malware. My hypothesis of the sample being a file infector was actually right!

Edit (12/29/25)

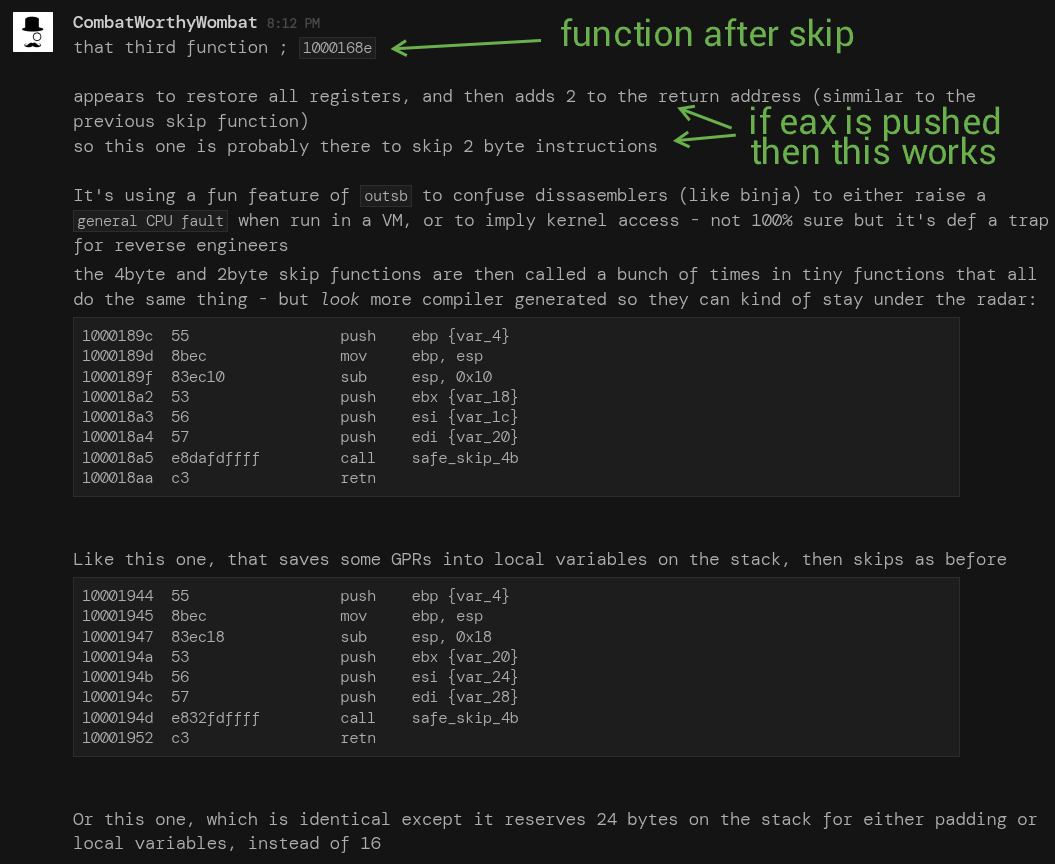

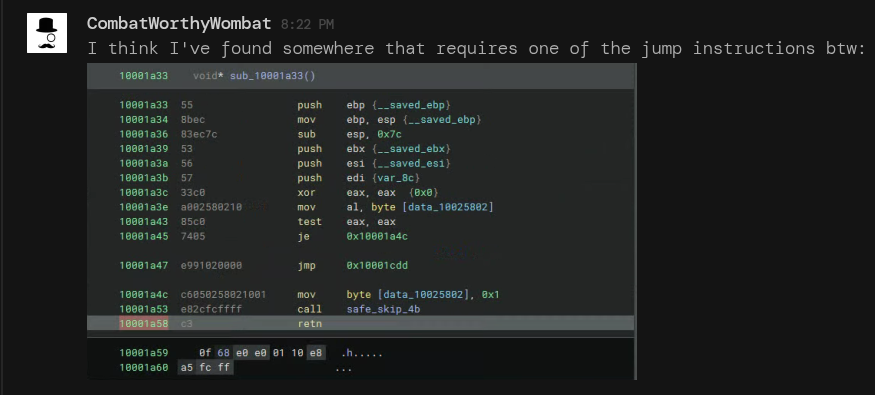

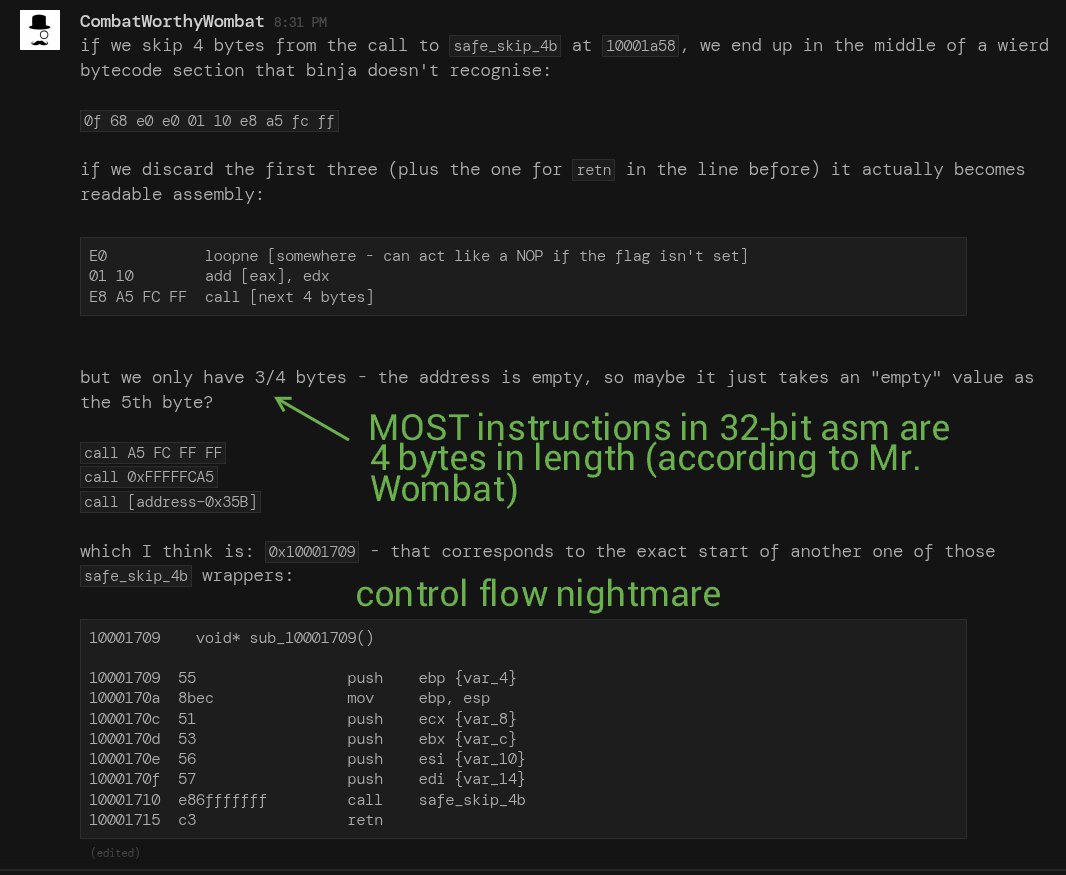

The marvelous CombatWorthyWombat from the Invoke RE server came to my rescue with some great findings on this sample that helped my understand the control flow nightmare that was occurring. They gave me their consent to post the conversation we had, which you can see below. I made a mistake in annotating the first image. The third function actually overwrites the return address on the stack, it does not require eax to be pushed!

If you look around points where the skip function is called, you will notice that there is dead code after the function calls, which will get called by this technique. Furthermore, for some functions, this also means that some instructions will be truncated or skipped entirely. We also need to keep in mind that we can't just script some behaviour to "cleave off 2 bytes from every occurrence of this call", as we also need to take into account even the dormant code segments.

The fix for this is to just write a script to cleave the correct amount of bytes (for the count they are incremented given the return address, when it is moved to a register). E.g. add eax, 0xy, where y = number of bytes skipped, then

`push eax`, OR check if the return address is overwritten (mov [esp-0xy], z, where z is the register containing the modified address.) Overall, it's just a massive pile of anti-analysis nightmares in our way.

I may (and should, for the sake of learning) write a script to patch this behaviour. I'm very happy that we at least solved the control flow nightmare of this binary, since I doubt this is something seen often, even in more esoteric samples (granted, this was compiled in 2012.)

Edit (01/06/2026)

The amazing Josh Reynolds himself streamed his analysis of this very sample on the Invoke RE twitch channel today! The VOD will be linked in a future edit, but I will post the script used to patch the obfuscated control flow.

import binaryninja

f = bv.get_functions_by_name('sub_10001684')[0]

for site in f.caller_sites:

print(f"Patching address: {site.address:2x}")

bv.write(site.address, b"\x90"*7)

Basically, we nop out all the skippped contents. 4 bytes are skipped for the call operation itself, 1 byte for ret, and a final 2 bytes for the actual return address modification.

Edit (01/13/2026)

The stream VOD for the analysis is live now! Go check it out!

Sources

LoadLibraryExA docs

FreeLibrary docs

WriteProcessMemory docs

TlsGetValue docs (some Tls* functions weren't noted here; this was the first discovered during analysis)

GetEnvironmentStrings docs

SetSecurityDescriptorDacl docs

OpenProcessToken docs

Privilege Constants

TTPs

T1033: Username enumeration

T1543.003: Creates service w/ CreateServiceA for persistence (and/or for elevated permissions)

T1012: Query Registry

T1112: Modify Registry

T1057: Enumerate Processes

T1027.007: Dynamic API Resolution

T1027.013: Obfuscated strings/control flow

IOCS

Sample SHA256: 9ee9e8e2522fec43a24f7c3742d01acad4cf6d8444a23d130b329f03f7103e35